On Friday, the thirteenth of July 1733, the New Spain Fleet left Havana harbor on its return voyage to Spain. Commanded by Lieutenant-General Rodrigo de Torres aboard the 60-gun navio, El Rubi, the flota consisted of three other armed navios, sixteen merchant naos, and two smaller ships carrying supplies to the Presidio of St. Augustine. The following day, after the vessels sighted the Florida Keys, the wind shifted abruptly from the east and increased in velocity. Lieutenant-General Torres, sensing an approaching hurricane, ordered his captains to turn back to Havana and to sail as close to the wind as possible, but it was too late. By nightfall of the fifteenth, all or most of the ships had been driven westward and scattered, sunk, or swamped along eighty miles of the Florida Keys. Four ships made it safely back to Havana. Another vessel, the galleon El Africa, managed to sail on to Spain undamaged.

Survivors gathered in small groups throughout the low islands and built crude shelters from debris that had washed ashore. Spanish admiralty officials in Havana, worried about the fate of the fleet, sent a small sloop to search for wrecks. Before the sloop could return, another boat arrived in the harbor and reported seeing many large ships grounded near a place called "Head of the Martyrs." Immediately, nine rescue vessels loaded with supplies, food, divers, and salvage equipment sailed for the scene of the disaster. Soldiers were on board to protect the shore camps and the recovered cargo.

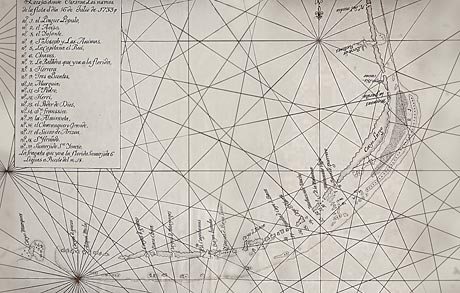

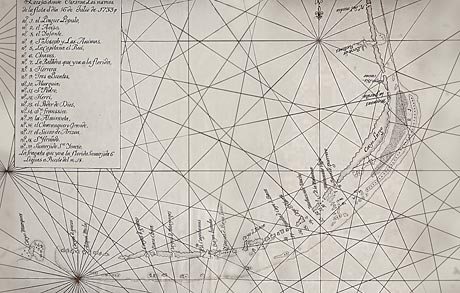

A Spanish salvors chart showing the locations of the 1733 Plate Fleet shipwrecks

Vessels that could not be refloated and towed back to Havana were burned to the waterline, enabling divers to descend into the cargo holds, and also concealing the wrecks from freebooters. The work continued for years, with the salvors working under the watchful scrutiny of guardships. The location of each shipwreck was charted on several maps. When a final calculation of salvaged materials was made, more gold and silver was recovered than had been listed on the original manifests, the tell-tale evidence of contraband aboard the homeward-bound vessels. In the 1960s, most of the wrecks associated with the 1733 fleet were relocated by modern divers. Although many documents relating to the Spanish salvage operations have been consulted, confusion still exists about the identities of some of the wrecks, since names and locations differ depending on the documents examined. Compared to the 1715 Spanish plate fleet that wrecked on the east coast of Florida, very little “treasure” has been discovered on the 1733 wrecks, a testimony to the successful salvage activities of the Spaniards. Unfortunately, some of the historical and archaeological value of these sites has suffered from insufficient recordkeeping on the part of modern salvors.

However, beginning in 1968 the State of Florida initiated a salvage contract program overseen by State appointed agents with archaeological oversight. The 1733 sites represent some of the oldest artificial reefs in North America, supporting complex ecosystems of marine life that have thrived generation after generation over the centuries. The real “treasure” of the 1733 fleet is the opportunity to visit the living remains of ships from an era long gone.

0 σχόλια:

Δημοσίευση σχολίου